Are 'Personal Operating Manuals' the Key to Making Flexible Work Work for Everyone?

Flexible work is so important to the current workforce that employees — specifically women — are leaving the workforce in droves to get it.

1 in 2 working women in the U.K. said they’ve left or would consider leaving a role if there was a lack of flexibility. LinkedIn coined the trend a “flexidus.”

Although flexible work has become more popular — even just as a job search buzzword — since the pandemic, 46% of women say that there’s still a stigma attached to flexible working, according to LinkedIn.

There’s little legal protection for flexible working, too. In the U.S., only a couple of states offer legal protection for flexible working — New Hampshire, Vermont and the City of San Francisco.

Currently, most U.S. employers “are not under any legal obligation to grant flexible or work-from-home arrangements unless the reason is that someone has a disability, or is caring for someone with one,” Brett Schneider, partner and chair of the labor and employment division at Miami law firm Weiss Serota Helfman Cole & Bierman told WorkLife.

Yet flexible work is something that a majority of employees obviously want. It’s also something that could have tangible benefits on employee health and productivity; 30% of women think that flexible work could improve their mental health, and 22% think they would thrive at work if they had more flexibility.

So what’s stopping employers if they know that this is what employees want — and even need to thrive at work?

It’s not necessarily because they think flexible work will affect their workforce’s productivity. Instead, it could be because they don’t know how to implement flexible work. There’s no rulebook or precedent for what flexible work looks like. What flexible work actually looks like on a day-to-day basis can differ greatly from one company to another, or even one team at a company to another.

Unfortunately, there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to making flexible work “work” for everyone.

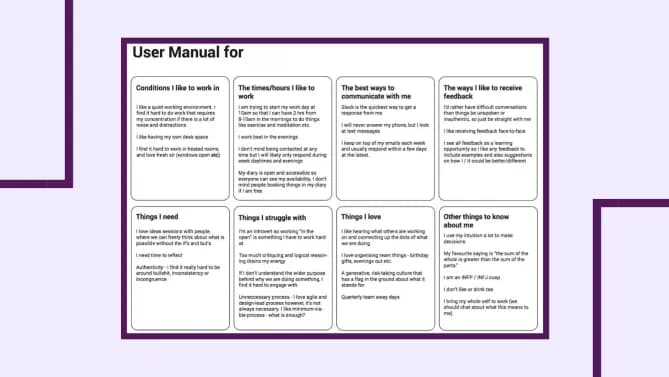

For flexible work to work, there actually needs to be personalization. That’s why “How the Future Works” by Brian Elliott, Sheela Subramanian and Helen Kupp suggest using “personal operating manuals” to figure out how to make flexible work function on a team level.

Personal operating manuals are common practice for teams that want to better understand their coworkers’ preferred communication style and ideal working environment. In this case, Elliot, Subramanian and Keep suggest including explicit norms and expectations each team member has for flexible work.

After establishing these guidelines, the team not only learns more about each coworker’s working style, but the team can settle on collaboration and flexible work times. They suggest teams set a three or four-hour break in the day where they can expect everyone on the team to be online to collaborate, whether that’s for a recurring meeting or a quick response message.

Personal operating manuals make the vagueness of flexible work concrete by setting expectations for how team members communicate and when they are and aren’t online — instead of assuming they’re on during a traditional 9-to-5 schedule or that they’re available during all hours. They inform teams on when they’re supposed to be available for collaboration and set aside the other hours of the day for flexible time.

Yes, personal operating manuals require extra work upfront, but they can ensure that down the road people are content with their flexible work arrangement and there’s a better work culture for the entire team. That’s the paradox of how flexible work can work: be rigid when creating boundaries, and enjoy the flexibility that comes after.

--

This article reflects the views of the author and not necessarily those of Fairygodboss.

What’s your no. 1 piece of flexible work advice? Share your answer in the comments to help other Fairygodboss members!

Why women love us:

- Daily articles on career topics

- Jobs at companies dedicated to hiring more women

- Advice and support from an authentic community

- Events that help you level up in your career

- Free membership, always